Annual report 2017

"In a global economy it is not only investment and profits that travel across geographical boundaries, but also worker solidarity"

At Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC), every day is an opportunity to advocate for those who stitch our clothes in the global garment and sportswear industries.

Since 1989, we have worked to empower garment workers by defending their fundamental human rights and demanding decent work conditions on their behalf. Our global alliance of trade unions and non-government organizations cover a broad range of perspectives and special interests – including women’s rights, consumer advocacy, and poverty reduction. Together, we educate and mobilise consumers, lobby companies and governments, and offer direct solidarity support to workers in their fight for a better life. With our mutual capacity development approach, members of civil society are equipped to advocate and lobby for social justice and human rights.

Much of the clothing we buy and wear is produced in regions of the world where raw materials are plentiful. But another, more troubling thread exists: These places are among the least likely to respect the fundamental rights of the young girls, women, and migrant women who comprise 85% of the workforce. Many work an average of 10 hours a day, 6 days a week to make ends meet. While this model generates economies of scale for garment and footwear industries, it reserves poverty wages, excessive overtime, harassment and abuse for an estimated 75 million laborers. For them, there is no sense of job security – and attempting to organise or protest is grounds for termination. A 3-month contract is merely a stepping stone to the next 3-month contract.

This must end.

Now more than ever, a growing proportion of consumers are calling upon fashion’s most popular brands for transparency on how and by whom their products are made.

Workers’ wages, their safety and their opportunities in this world are directly affected by the business behind fashion’s biggest brands – like H&M, Primark, and Uniqlo.

With women at the forefront of garment production, we fight for their dignity with safe factories, the freedom to organise, and living wages for all.

In this fight, success is not won without persistence. Our prospect for victory relies on our belief in justice and in the power of people. In fact, at the brink of 2018, our global alliance encompasses nearly 30 years of progress among 200 diverse organisations.

In garment-producing countries and consumer markets, our grassroots network identifies local violations and objectives and transforms them into global actions. We are proficient and stringent in assessing major brands for signs of injustice in their supply chains, and the perspectives of garment workers are leading in our proposed solutions.

Wage theft was our core focus in 2017. This endemic problem often occurs when a brand halts production and thus bankrupts the manufacturing facility. In this situation, workers are unlikely to receive accumulated severance payments or back wages of any kind.

Equally prominent was our focus on safety – specifically in Bangladesh following the 2013 collapse of Rana Plaza, where scores of workers were left injured and penniless and more than 1,000 people perished.

Included in our accomplishments is our continued dominion for transparency among the supply chains of prolific brands. We believe public information is essential and powerful. When armed with the facts, workers, activists, and consumers are fit to hold brands accountable for violating labor rights in their supply chains and factory practices. Click the images below to see what’s possible when unions, workers, and consumers unite for human rights on behalf of garment workers.

Global cooperation is critical to our cause, as many nations – including democratic ones – are narrowing their tolerance for civil society engagement and responding to its participants with hostility and violence.

Those who stand to defend human rights are up against repressive policies, laws, practices, intimidation and violence that impede their freedom to organise, assemble, operate, raise and secure funds, or even express dissent.

The struggle for inclusive and sustainable progress is particularly unyielding for grassroots and community-based movements, women’s and gender justice groups, and those working to advance human rights. We believe we can work to overturn this reality in all corners of the world with our network of solidarity – with a leading role for the workers whose stories inspire courage in the fight we share.

Urgent Appeals

An urgent appeal is a request for Clean Clothes Campaign to support garment workers in concrete cases of rights violations. When Clean Clothes Campaign takes up an urgent appeal, we develop a strategy together with local partners, and we frequently form broader international coalitions. We always first try to find a “behind the scenes” solution together with the sourcing companies, the factory management and, at times, with public authorities. Only if this approach does not work – and if local partners agree – do urgent appeals cases become subject of public campaigning.

'We demand what is rightfully ours. We only demand the compensation for our labour. Nothing else, nothing more,' says Yeliz Kutluer, a former Bravo Tekstil factory worker who lost her job shortly before giving birth to her first child.

Imagine working for three months without pay, then losing your job with no severance or back wages. This injustice was a reality for workers upon the shutdown of Bravo Tekstil, a factory complex in Istanbul, Turkey. Bereft of their wages, workers left messages (“I made this product, but I didn’t get paid for it”) in the garment pockets they manufactured. It wasn’t long before consumers of Zara, Next, and Mango discovered the communication and took to the internet, gaining the attention of an international audience.The story reached millions of people and300.000 backed a petition that demanded Zara, Next and Mango to pay the wages they owed.

“Brands are principal employers. They have proven time and again that they control every aspect of their orders to their suppliers. Therefore, it is clear that it is in their power to make sure that all workers who produce their apparel receive their monthly wages. Morally they must do so,” says Bego Demir of Clean Clothes Campaign Turkey. By the end of 2017, Bravo workers remained without justice.

'It’s unjust that workers who made Uniqlo clothes are made to suffer, while the Uniqlo brand continues to grow and thrive, generating billions in profits. The money we are owed, we earned over years of working hard to make Uniqlo clothes, and to refuse to pay us is tantamount to wage theft,' says Warni Lena Napitupulu, a woman worker formerly at PT Jaba Garmindo, a factory which suddenly closed after the Japanese mega brand Uniqlo pulled their orders.

When several garment factories in Indonesia, Cambodia, and Turkey closed without warning in December, exploited garment workers and campaigners took united action against Adidas, Mizuno, Uniqlo, Zara, and Marks & Spencer for their thefted wages. Inspired by those who lost their jobs at Bravo Tekstil, workers and activists enclosed their story in the clothing they made – later discovered by holiday shoppers around the world. Protesters took to the streets in Indonesia, Japan, Turkey, Germany, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and Hong Kong, implicating the high-profile brands for wage theft.

The garment industry is a race to the bottom. As brands take liberties in their chains of supply, it is workers – not consumers – who pay the greatest price. When a garment brand halts production at one factory for another, where they can further minimize their operating costs, workers receive no warning or explanation. The ramifications of this trend are dire and long-lasting for workers, especially for older women who may never secure another job.

'If brands are taking the necessary steps to prevent labour abuses in their supply chains, you’d expect them eagerly wanting to share detailed information about the factories and workers who make their clothes, ’ says Christie Miedema from Clean Clothes Campaign.

As more and more brands disclose the numbers behind their supply chains, Consumers are raising their expectations for transparency – and expect brands to take responsibility. Our #GoTransparent campaign rallied 70,000 people to demand manufacturing details from Armani, Forever 21, Walmart, Urban Outfitters, and Primark.

As one of nine organizations in the Transparency Pledge Coalition, we urged dozens of brands to consider adopting our minimum standard. Per our proposal, 17 large brands released information about their manufacturing procedures. Many more agreed to increase their transparency to a relative extent. Read more in our report.

In a global economy it is not only investment and profits that travel across geographical boundaries, but also worker solidarity,’ says Sri Lankan FTZ&GSEU General Secretary Anton Marcus

When fundamental rights are on the line, international support and solidarity are true beacons of hope. At a pair of factories in Sri Lanka, management and employees held a referendum on the long-disputed topic of safety. In the end, workers voted for – and won – recognition for collective bargaining. Subsequently, the workers involved the Free Trade Zones & General Services Employees Union (FTZ&GSEU) to weigh in.

After years of conflict and opposition, this resolution is a testament to the empowering nature of international solidarity as supported by trade union.

‘After a period of conflict, we can now negotiate as equals in a respectable environment. This outcome was possible because of the resolve with which the workers stood together and remained confident that collective strength can safeguard their rights, says Anton Marcus.

'llegal closure is a weapon of last resort by employers in their union busting bag of tricks. Faremo is not the first and probably not the last,' Partido Manggagawa (Labour Party) chairperson Rene Magtubo

Philippine workers had recently established a union when Hansoll Textile halted all production at the Farema International factory in November 2016. While owners attributed the closure to a deficit in orders and profits, workers discovered the business had moved to Hansoll factories in Vietnam and Cambodia. The scandal united 800 individuals in international solidarity to picket for three months until they reclaimed their owed wages the following February.

“We owe this victory to our members' determination to fight, and the solidarity of fellow trade unions and international labour rights advocates,” says Faremo labour union president Jessel Autida.

A living wage for all, right H&M?

In 2013, H&M pledged to provide its 850,000 garment workers with a living wage by the end of 2018. Four years later, we voiced our anticipation of this promise – so long as H&M follows through.

A living wage is critical for garment workers to afford proper housing, access to medical care, transportation, education, a healthy diet for their families, and discretionary income for the unexpected. Without it, this population of mostly women is obligated to compromise their most basic needs for the foreseeable future.

While H&M’s goal is ambitious, it is not impossible for a company of its size, profit, and power. Absent from their pledge, however, is a tangible roadmap – one that indicates how they’ll reinvent their supply chain to include higher wages, freedom of association, and zero tolerance for gender-basedgender violence. We continue to keep watch on behalf of H&M garment workers.

Safety first for Bangladeshi workers

The dust has settled at Rana Plaza since its collapse in 2013, but the destruction is not forgotten. In response to the deadliest incident in the history of garment manufacturing, brands and unions are collaborating to create the Accord on Fire and Building Safety. Five years into development, signatories expect an additional three years of planning – until 2021 or until local bodies assume responsibility.

As one of four witness signatories to the Accord, we urged Bangladeshi brand manufactuers to participate.

Our agenda also includes justice for those who are injured or killed while working. When a factory boiler exploded in July, we integrated boiler inspections in the Accord programme and paved the way for a pilot study by the Accord Steering Committee.

Our focus grew to include factories outside of the Accord, where brands are less likely to compensate workers for safety incidents. Per the Employment Injury Insurance campaign, workers who experience health issues at work receive financial support, as do families who lose their bread-winning loved ones.

Major crackdown of workers in Bangladesh

“This is the biggest setback for the garment industry since the collapse of Rana Plaza in 2013 and might cause the Bangladesh government to lose their key export market. Its not possible to talk of a safe or sustainable industry in Bangladesh when even peaceful attempts to ask for workplace improvements are met with such disproportionate violence and repression. Garment workers in Bangladesh have the unequivocal right to organize and must be paid a living wage on which they can survive,” says Sam Maher from Clean Clothes Campaign

On behalf of the garment workers, trade union leaders and activists who were arrested during Bangladeshi protests in late 2016, CCC joined global trade union federations in the #EveryDayCounts campaign, calling for the immediate release of those persecuted for protesting. In response, five leading apparel companies – H&M, Inditex (Zara), C&A, Next, and Tchibo – canceled their respective speaking engagements at the Dhaka Apparel Summit, organized by the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA).

Owed billions of dollars in annual garment purchases among Bangladeshi manufacturers, #EveryDayCounts led to the release of all workers and compensation and reinstatement for a portion of workers. However, many cases of unfair dismissals and charges against union leaders were not resolved. The constant fear of arrest continues to impede Bangladeshi garment workers in their fight.

Bangladesh protests and the European Union’s role

In December 2016, news of worker repression broke out in Bangladesh. Following the temporary closure of approximately 60 factories, employers dismissed thousands of workers and had over thirty labour leaders arrested. Together with the EU, fashion brands, national governments and other stakeholders we urged the Bangladeshi government to improve labour conditions in compliance with the Sustainability Compact.

"The recent crackdown and the structural shortcomings of Bangladeshi labour policy show that three years on, the government is still far from realizing the promises made under the Sustainability Compact," states Ben Vanpeperstraete from Clean Clothes Campaign. "The European Union must not remain silent in the face of this continued failure to respect workers' rights.”

Read our white paper on the Sustainability Compact.

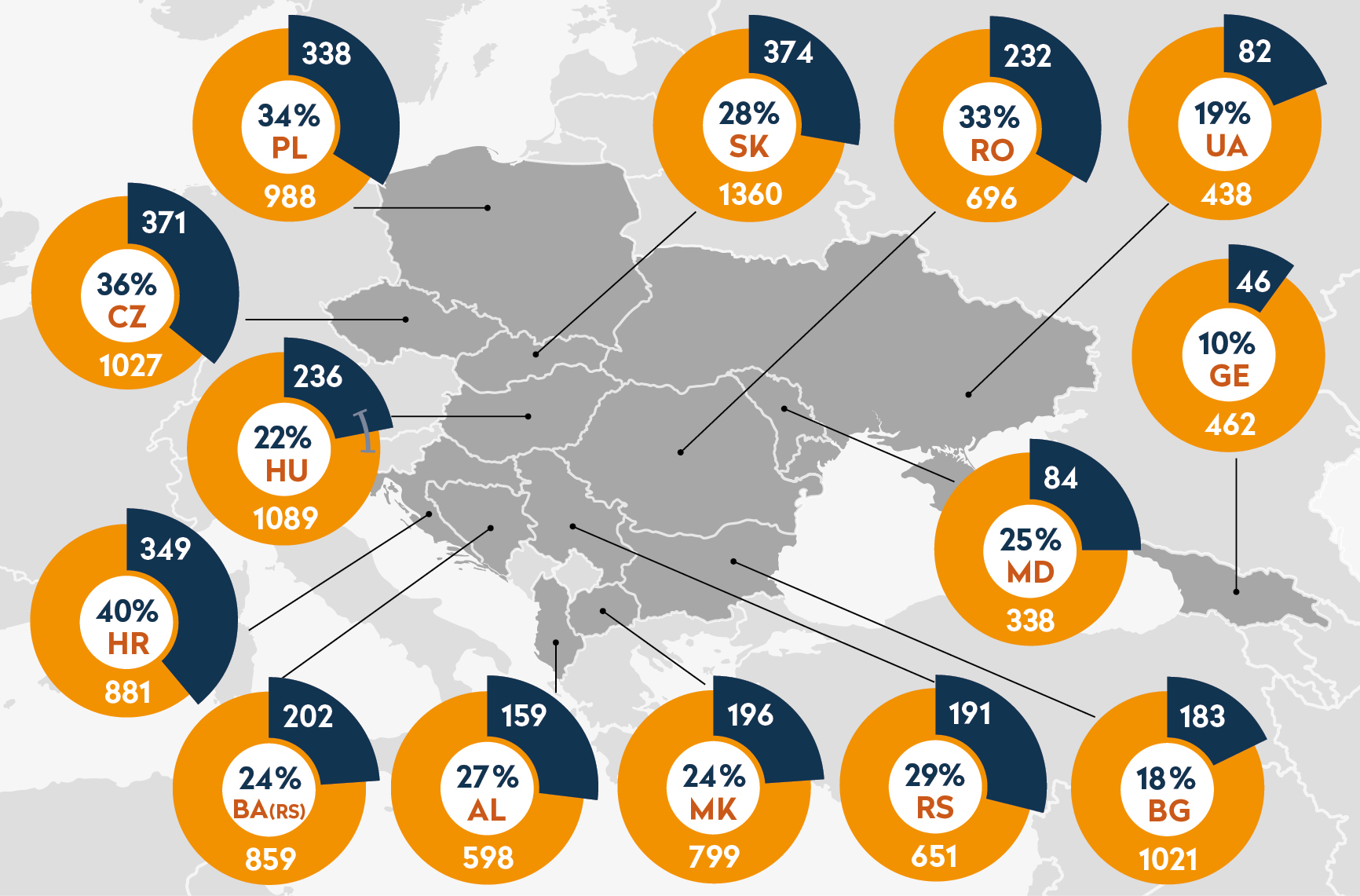

Made in Europe

Global fashion brands pay the lowest wages to workers in Eastern and South-Eastern European countries While consumers may interpret “Made in Europe” to mean “Made in fair conditions”, the majority of the region’s 1.7 million garment workers are living in poverty with significant debt. At the factory they face perilous conditions and forced overtime.

In our report, Europe's Sweatshops, we document endemic poverty wages and insubstantial working conditions in the garment and shoe industry throughout Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. As one example, those working overtime in Ukraine received a monthly payment of EUR 89 – five times less than a living wage – for brands including Benetton, Espirt, GEOX, Triumph, and Vera Moda.

The report also includes data on behalf of workers in Ukraine, Serbia and Hungary.

“When Serbian workers ask why in the heat of summer there is no air-conditioning, why access to drinking water is limited, why they have to work again on a Saturday, the answer is always the same: 'There's the door', says a worker quoted in the report.

Regarded as the fifth largest source of pollution, the fashion industry continues to subvert even the most assiduous practices in recycling and sustainability. Fast fashion contaminates the air, water and land at every step in the garment life cycle – treating cotton with pesticides, dyeing with hazardous chemicals, releasing microplastics with each rinse, burning leftover collections, and disposing mass amounts of low-quality fashion in land-fill.

The true impact of these practices is felt most among the world’s most poor, vulnerable, and oppressed populations, especially young women and migrant women. For those who work in garment factories, the poverty wage relegates many to live in depraved environments without accessibility to basic needs. The factory’s polluted waterway may be the very source these individuals and their families rely on for drinking and bathing.

With special interest in young women and migrant women, we believe transparency is the catalyst for maintaining an ethical supply chain that provides living wages and fair working conditions for all. This foundation will allow garment workers the means to make ends meet for their families, and can empower consumers to demand a new standard for sustainable, ethical clothing.

Our holistic approach aligns with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

2017 in number

- 309,267 people demanded justice for Bravo workers

- demonstrations in 14 countries demanded the release of worker leaders in Bangladesh

- almost 70,000 people urged brands to #GoTransparent

- Twitter and facebook 13652 and 46010 followers respectively.

- our website was visited 424.846 times by 153.938 people, 28.9% users of which visited on mobile

- Clean Clothes Campaign was mentioned around 300 times in English-language mediaTw

Highlights in the media

Reuters on the Bangladesh protests

Open Democracy reports on our Made in Europe report

The Guardian on Louis Vuitton's production in Romania

Interview with CCC researcher Oksana Dutchak from the Ukrainia

Organisation

Following the creation of regional coalitions in South Asia ( Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) and east Asia (Hong Kong, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea), organisations in South East Asia decided during a regional meeting on Bali in May 2017 to also form a coalition (Birma/Myanmar, Cambodia, The Philippines, Indonesia, Maleisia and Thailand). Workers in these regions now have direct influence over CCC’s international policies.

Four unions and four NGO’s in Indonesia formed a national coalition, the first in Asia!

During a meeting in Budapest in Spring 2017, Eastern and South Eastern European organisation renewed their decision to be part of the European coalition. This coalition consists now of national coalitions and organisations in Albania, Belgium, Germany, Finland, France, Georgia, Italy, Croatia, Macedonia FRY, The Netherlands, Norway, Ukrain, Austria, Poland, Romania, Servia, Slovakia, Spain, Czech Republic, Turkey, United Kingdom and Switserland. In Croatia a new coalition was formed.

Two coalitions, Denmark and Ireland, seized to exist in 2017.

At the European regional meetings in May in Madrid and November in Zagreb, the coalition worked hard to bring all European coalition together int one region. Since countries with garment production facilities need different strategies, the region formed a European Production Focus Group.

The Dutch Clean Clothes Campaign and the Clean Clothes Campaign International Office share the same office space and administrative support. Clean Clothes Campaign does not have a director or a management team. Decisions on working conditions, such as salary and overtime policy, are jointly taken by the personnel.

Board

The Schone Kleren Campagne / Clean Clothes Campaign governance principles are set out in the Articles of Association.

The board consists of five voluntary members:

Mr. Evert de Boer (chair)

Mr. Sjef Stoop (treasurer)

Ms. Nina Ascoly

Ms. Hester Klute

Mr. Just van der Hoeven

Finances