Keep all workers safe

The independent safety inspections and enforceable safeguards of the Accord have been immense importance to ensure workers do not have to risk their lives going to work, but many workers across the world continue to risk their lives in unsafe buildings, because the brands sourcing from their factories have not signed the Accord, or the Accord does not cover their factories. It is time to ensure safe factories are no privilege, but that every worker can be sure the building they work in is safe. This is what needs to happen to make that a reality.

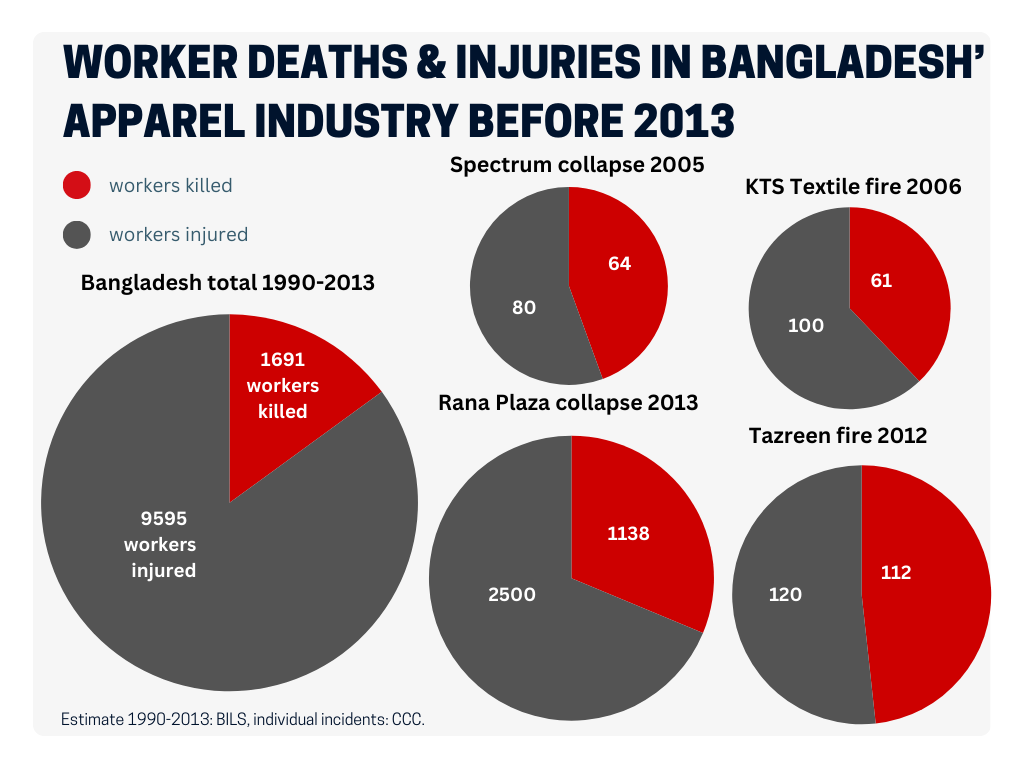

The Accord started in Bangladesh, where over a decade of fires and collapses, which ended with the Rana Plaza collapse of 2013, showed the inevitability of a binding agreement to international brands. Despite concerted campaigning by unionists in Pakistan and Bangladesh to expand the Accord beyond Bangladesh to other high-risk countries, it took ten more years to expand to Pakistan in 2023.

The 2023 International Accord has committed to expand to other countries, and it should do so quickly, because around the world, workers continue to get injured and die in the workplace, as our tracker below shows all too well.

Currently, workers in India, Turkey, Vietnam, Egypt, Cambodia and elsewhere have no independent complaint mechanism to turn to, nor are their factories regularly checked in independent inspections. Expansion of the Accord to their countries will make factories safer for all workers in supply chains of Accord signatory brands. These numbers are based on media monitoring and therefore are just the tip of the iceberg, because many incidents never make it to the media.

Before and after

Before 2013, garment factories in Bangladesh were notoriously unsafe. Workers' deaths and injuries in the garment industry and related industries were frequent and the death toll was high. Although brands knew about these unacceptable risks to the workers producing their clothes, it took unions and labour rights organisations, including the Clean Clothes Campaign over a decade to make brands listen. By 2012 there was a binding agreement with two brands' signatures on it, but the agreement would only take effect after four brands signed. Despite years of intensive dialogue and public pressure, all other brands waited until after the worst happened: the Rana Plaza collapse finally shook them awake. The Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, that was based on the binding agreement on the table, was signed by over 200 brands.

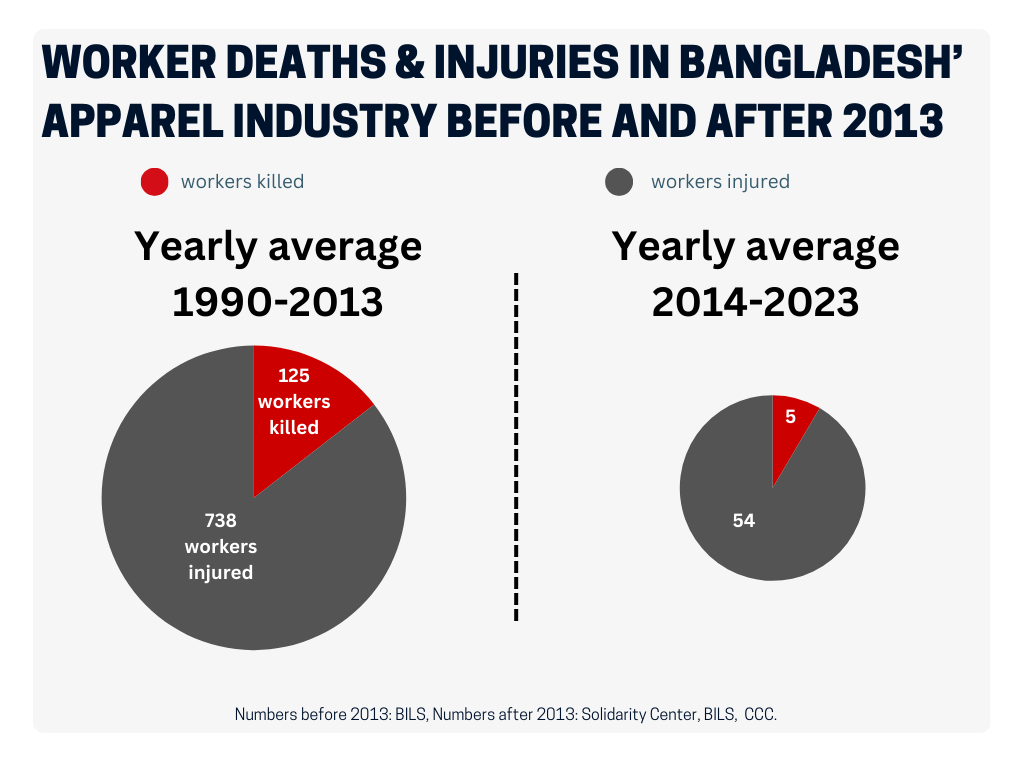

The Accord's independent inspections, its worker trainings and worker complaint mechanism made factories safer for over 2 million workers in 1600 factories. Key is its legally enforceable nature, which enables unions to sue brands that are not keeping to their commitments in court.

Locks were removed from doors and fire-rated doors installed. Structurally unsafe buildings were evacuated until they were declared safe again. Factories' faulty electrical systems, a frequent cause of fires, were checked and made safe.

As a result, the amount deaths and injuries went down drastically, but many workers still are not safe at work: not in Bangladesh and even less so around the world. Not all workers are covered by the Accord. Find out what needs to happen to make sure that no worker around the world has to fear for their life upon entering the factory they work in.

1. All brands must sign the Accord

Over 200 brands have signed the Accord, but there are still brands who prefer to leave their workers at the mercy of the corporate-led systems that failed to protect the workers in the Rana Plaza factories and other major factory incidents. Have a look at our brand tracker to see which brands are still dodging responsibility and how you can take action to convince them.

2. The Accord must quickly expand to other countries

3. The Accord must also cover workers deeper in the supply chain

Currently, signatory brands to the Accord in Bangladesh are only obliged to list the "first tier" of their supplier factories. This means that only the facilities that make the end product that the brand eventually sells, are covered. But before a t-shirt is cut, stitched, trimmed and folded, a lot of workers have handled the fabric. Millions of workers toil in spinning mills, dyeing facilities, and other related industries without independent factory inspections and worker safety trainings, even if the are working in the supply chain of an Accord signatory brand. In the past three years, Clean Clothes Campaign recorded around 20 incidents in textile, spinning, and fabric mills in Bangladesh. These incidents are included in the total numbers on this page and make up about 22% of the total amount of recorded incidents in the garment, textile and related industries sector. This is a conservative estimate. It is high time that the Accord's scope is expanded to make sure that signatory brands are also invited or even obliged to bring factories deeper in their supply chain under the purview of the Accord.

A gas pipe explosion - an example

On 8 February 2024, 14 workers were injured in a gas pipeline explosion in the Crony Group, which includes Crony Apparels Limited - an Accord covered facility producing for Accord-signatory Matalan and non-signatory Tom Tailor, and Crony Textile Unit instead: a sister company across the street - deeper in the supply chain and therefore not covered. This means that the facility was not checked by independent inspectors beforehand, that workers have no avenue to complain if they see safety violations and that the facility will not receive a post-incident inspection to indicate what needs to remediate to ensure that the results of the blast do not endanger more workers and that such an incident can never happen again. It is high time to bring facilities deeper in the supply chain under the purview of the Accord.

4. Workers in Bangladesh must be able to continue to trust the system

In 2020, the implementation of the Accord on the ground in Bangladesh was taken over by the Ready-Made-Garment Sustainability Council (RSC), consisting of Accord signatory brands, unions, and factory owners. Since then labour rights advocates have voiced concerns about the growing influence of employers on the Accord operations in the country, including on the level of transparency exercised, the measures taken against factories that do not carry out the safety remediations as ordered after the inspections, and the complaint mechanism.

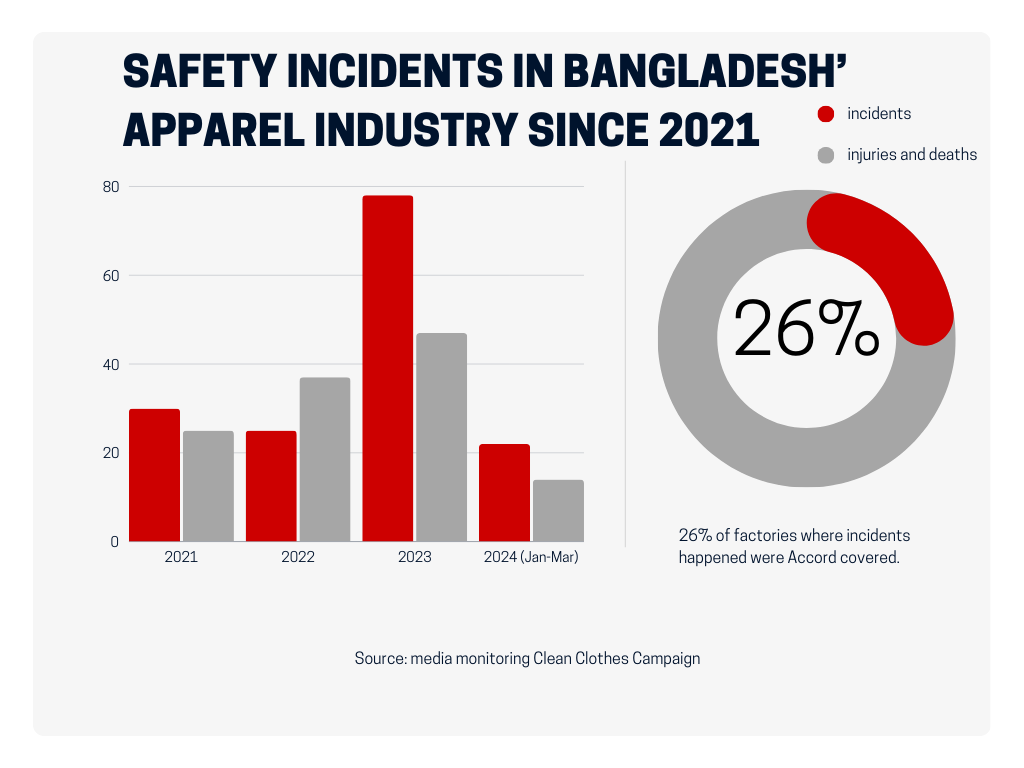

Incidents and injuries among workers have been on the rise in Bangladesh since 2021 and while most of them occur in factories that are not covered by the Accord, it is important to remain vigilant to ensure that workers in Bangladesh can trust the local operations going forward.

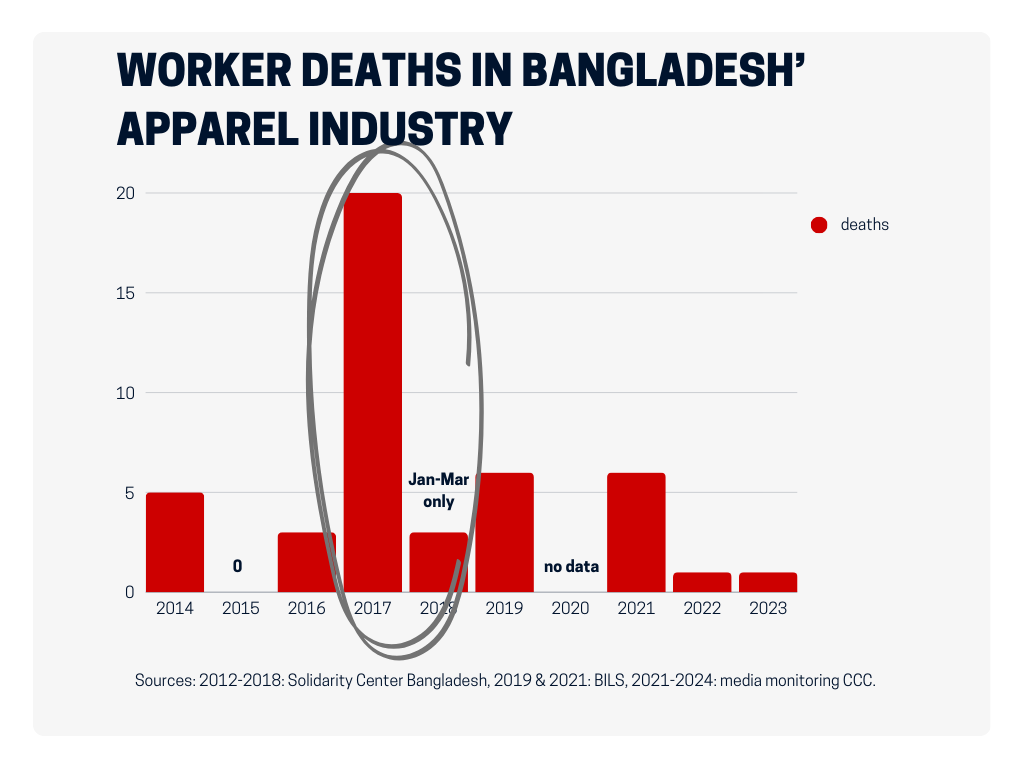

One of the issues that has slowed down, but which workers vitally need to remain safe in their factories, are boiler inspections. When the Accord first started in 2013, boiler inspections were not included in its mandate and left to the authorities in Bangladesh. The relevant department was however chronically understaffed, which meant that workers continued to be at risk of boiler explosions. This became painfully clear in 2017 when a boiler exploded in the Accord-covered Multifabs factory, killing 13 workers - making it de deathliest incident in the Bangladesh garment industry of the past decade.

After a pilot in 2018 it was agreed that that boiler inspections would be fully covered by the Accord programme. Progress is however very slow, by 2024 only 71 factories have had a full boiler inspection. Excuses continue to be made about how boiler inspections will slow down production as inspection can only be done on a cooled-off boiler.

Workers' lives should be more important than profits and it is vital that the boiler inspection work soon picks up speed to prevent the next Multifabs from happening.

Colofon

1. Statistics

Solidarity Center (2012-2018)

Clean Clothes Campaign (2021-2024 - unpublished media monitoring)

2. Incident tracker

Methodology: Unless otherwise noted, information on the safety incidents is from news reports. Brands were identified primarily through import records and brand disclosure. Because some apparel brands and most textile companies refuse to reveal their supplier factories, some of the factories where we were not able to identify buyers may also be supplying international brands and retailers. We welcome you to submit suggested additions to this timeline, or corrections, to info@cleanclothes.org; please provide information sources when doing so.

Recommended resources:

- Text of the International Accord for Health and Safety in the Garment and Textile Industry agreement

- Text of the Pakistan Accord on Health & Safety in the Textile & Garment Industry

- Signatories to the International Accord and the Pakistan Accord

- Overview of brands that have not yet signed the Accord

- Witness signatory statement on the start of the RSC in 2020