Poverty wages

We want everyone working in the garment industry to be paid a wage they can live on. The UN recognises a living wage as a human right, yet the current reality means millions of garment workers are systematically exploited as a source of cheap labour. Since the birth of the industry, garment workers all over the world have been forced to live in poverty, to the detriment of not only their own well-being but their communities and economies as well.

The problem

The global garment industry has doubled over the past 15 years and is powered by an estimated 60 million-strong workforce. The deprivation that the vast majority of these workers and their families face on a daily basis stands in stark contrast with the huge profits reported annually by global fashion brands.

Workers’ wages represent only a fraction of what consumers pay for the clothes because of deep-rooted structural power dynamics. A well-known example is the national kit of the England football team at the 2018 World Cup, embellished with a well-known sportswear brand logo and the most expensive England kit ever. They were sold to fans for as much as €180 – while the workers in Bangladesh who made them were earning less than €2 per day.

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights clearly state the role and responsibilities of businesses to respect the human right to fair wages. This responsibility “exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations ... And it exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights.” In other words, in cases where legal minimum wages fail to meet the minimum subsistence level (living wage) for workers in production countries – businesses have an obligation to remedy state failures.

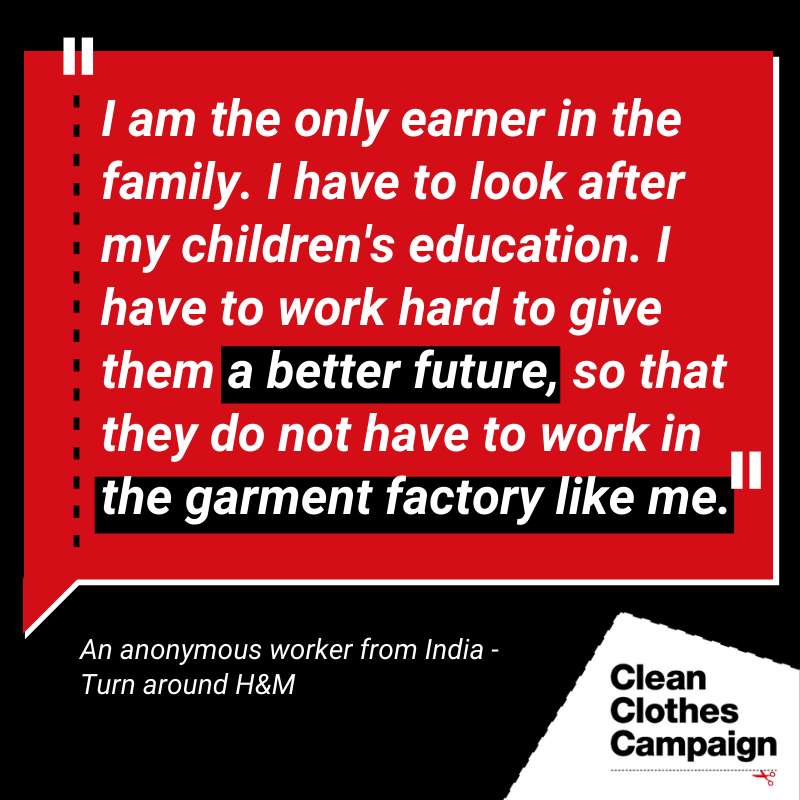

Yet our ongoing research shows that no major brand can prove all workers in their supply chain earn a living wage. The same holds for fast fashion, luxury brands and worker apparel alike. No garment or sportswear company recognises that brand business practices have a direct effect on workers’ wages, leaving millions of workers deprived of not only wages but sleep, access to health care, safe transport, the ability to live with loved ones, adequate food, education, even time poverty from needing to work extra hours. The financial difference fair business practice would have for brands is minuscule compared to the difference fair wages would have on workers' lives.

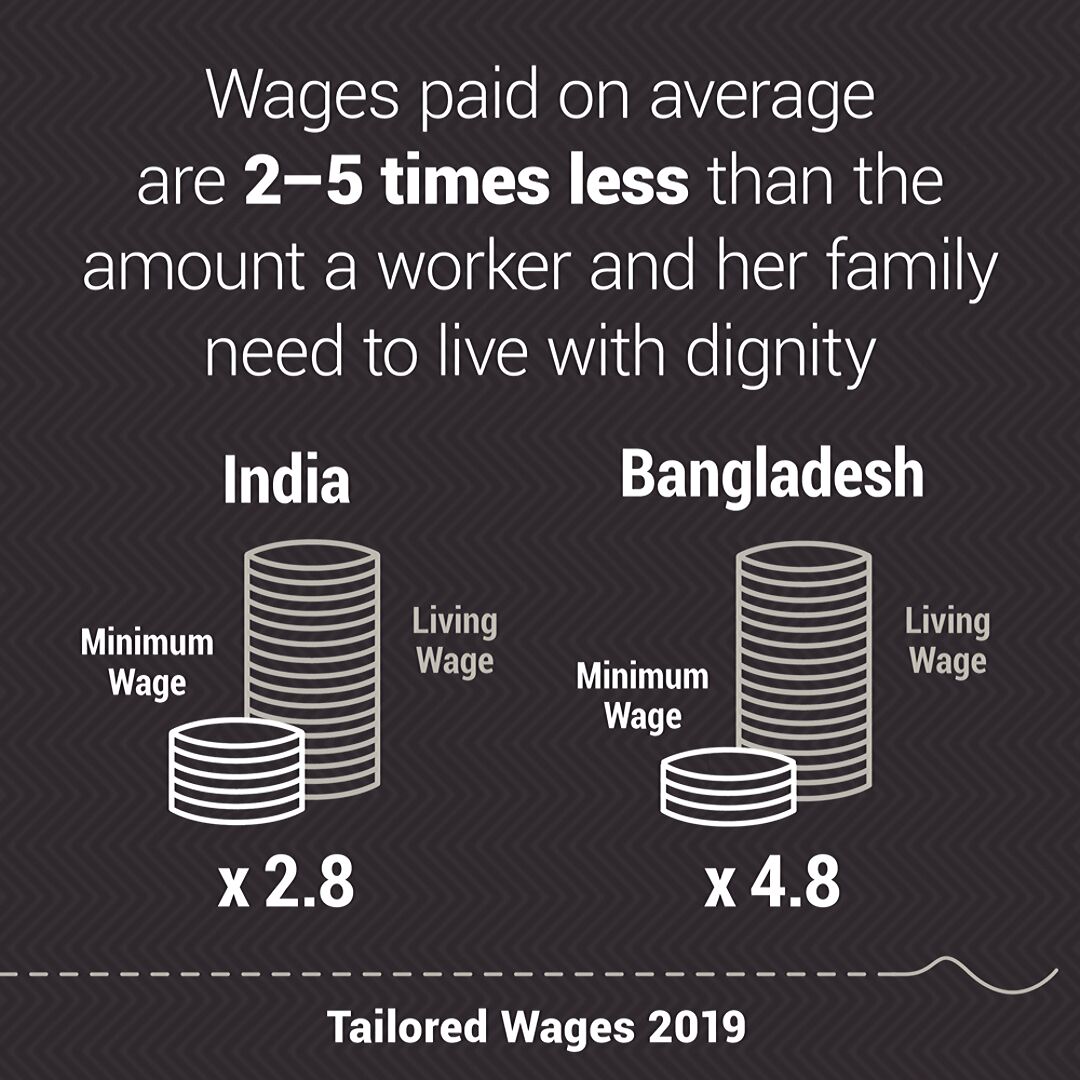

The right to a living wage has been recognised by the Council of Europe and by the UN in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, among others, but it is not respected in global production supply chains, even where legally set minimum wages are in place.

What we do

In order to reach a living wage, companies have to commit to fairer purchasing practices. If the solution rests on the factories and production country government policies then brands will always relocate to cheaper regions. Only when brands commit to paying more for orders can factories properly cover the costs of production, including labour.

Our work revolves around asking companies to use living wage benchmarks when calculating order prices. By putting a figure on the living wage, the labour cost can be calculated and embedded into pricing breakdowns, and companies can use this to be sure that suppliers are receiving enough to pay a living wage. If enough companies do this, production-country governments are given a clear signal that putting up the minimum wage to a living-wage level will not risk loss of business.

Living wage benchmarks

The Clean Clothes Campaign is part of the Asia Floor Wage Alliance, an alliance of Asian trade unions and labour groups, which has calculated a living wage formula for Asia. We feel this figure and methodology is the most robust, independent calculation for a living wage currently available, and is a vital tool in benchmarking what companies and governments should be aiming to achieve in terms of actual wage figures for workers. It is calculated based on some key assumptions that we believe must always be central to a living wage:

• A living wage is always a family wage. In most production countries, the pension and insurance schemes are not sufficient and public care services are often absent. A genuine living wage must therefore take that into account and at least partially cover the basic needs of unpaid caregivers in the household.

• A living wage must allow for savings. Without this, workers remain in a vulnerable situation, are not able to make mid- and long-term plans in their lives and are at risk of ending up in debt when additional unforeseen financial expenditure is needed.

• A living wage has to put a floor, not a ceiling, on wage payment and secure a minimum income for all workers. Ideally, a living wage should have a regional approach so as not to increase wage competition between countries, instead increasing the base wage level for all workers.

Freedom of Association

The commitment to a real living wage benchmark from companies also opens up space in wage negotiations between workers and factory owners. Currently, factory owners will say they have no choice but to keep wages low due to the low prices paid by buyers. In many cases this means that workers are under threat of losing their jobs or risk physical harm if they ask for higher wages. But if unions or worker groups know that brands being produced in their factory have committed to a specified living wage figure, these negotiations are opened up, and a living wage becomes a possibility.

Background

Poverty pay is one of the most pressing issues for workers worldwide, and it is embedded systemically in the global garment and sportswear industries. Companies have relied for decades on this system of poverty pay and exploitation, justifying the outsourcing of cheaply paid assembly work with the need to remain competitive in the global market and to offer cheaper prices to consumers.

Governments have kept minimum wages low under pressure from brands and retailers in a bid to create jobs and provide an economic boost to their state economies.

As a result, minimum wage, where it exists as a legally binding standard, is not the same as a living wage. What the minimum wage amounts to differs per country, but in almost all production countries, it is far from sufficient to provide for workers’ and their families’ basic needs. For instance, the Stitched Up report published by Clean Clothes Campaign in 2017 showed that there was a large gap between the legal minimum wages in Eastern/South-Eastern Europe and Turkey and what a worker would actually need to provide for themselves and their family.

Being paid poverty wages forces workers to work long hours to earn overtime or bonuses. They cannot risk refusing work due to unsafe working conditions, and they cannot take time off when they are ill. Workers often have to rely on loans to make ends meet and have no savings. If they find themselves out of work or faced with unexpected expenses, they are thrown into deep poverty.

There’s a host of related problems, such as poor housing, poor nourishment, inadequate access to health care, the risk of child labour, occupational accidents and violence against women.