Unsafe workplaces

Most garment workers do not feel safe at work. Not only are they working in dangerous buildings, but workers are routinely exposed to inhumanely high temperatures, harmful chemicals and physical violence. We are involved in programmes to help prevent injuries and deaths on the job and appeals for compensation for workers involved in incidents that could have been prevented.

The problem

The search of the global garment and sportswear industries for the lowest production costs comes at a high price: the health and safety of workers. After more than a century of work as CCC, developing national regulations and international conventions, workers continue to lose their health and lives while stitching our clothes.

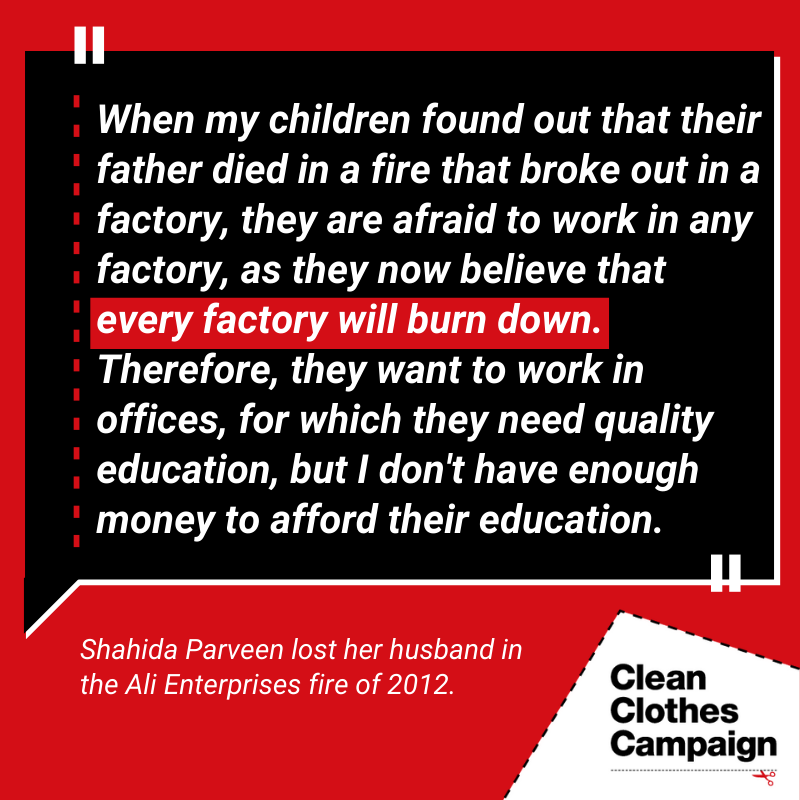

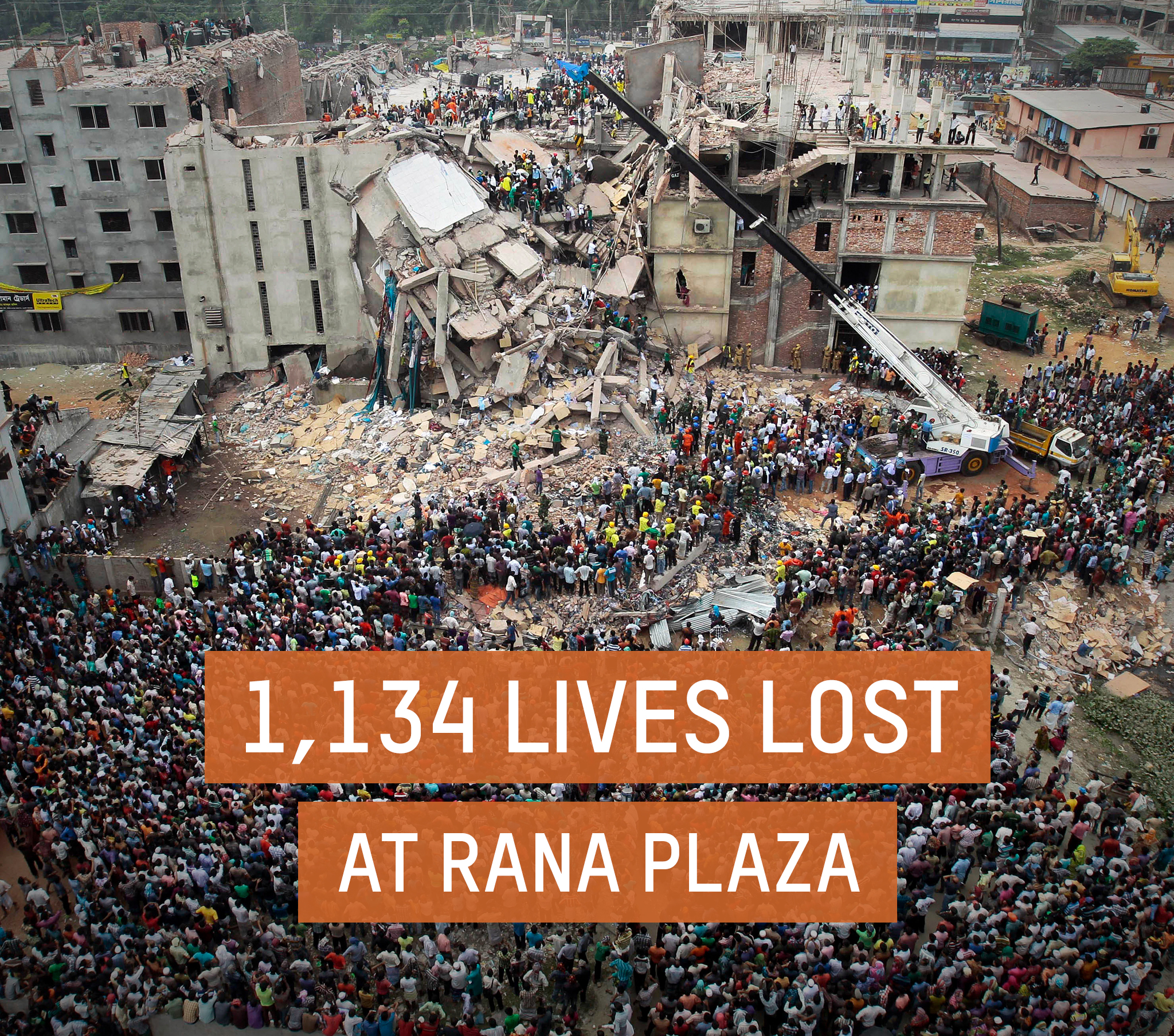

World-wide attention on worker safety in the garment industry has grown enormously since three devastating accidents that killed thousands of workers and shook the world: the factory fires of Ali Enterprises in Pakistan and Tazreen Fashions in Bangladesh, both 2012, and the Rana Plaza Collapse in 2013, Bangladesh.

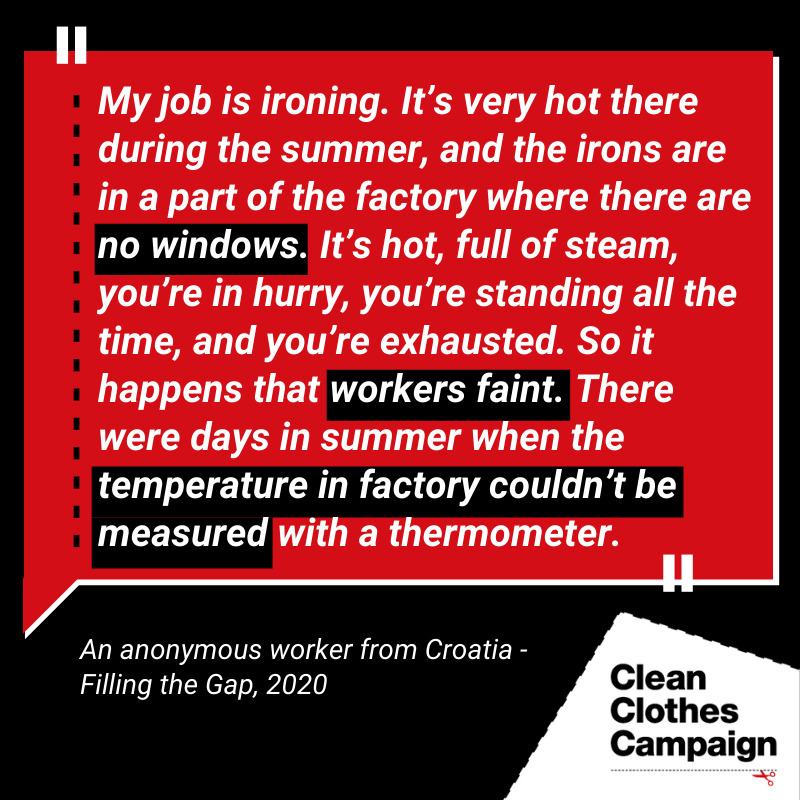

But workers are not only threatened by unsafe buildings. Dangerous practices, such as the unprotected use of chemical substances or sandblasting, continue to be common in the industry. And even workers behind the sewing machine are exposed to health hazards, such as noise, high temperatures and repetitive motion. Fainting is common in factories where workers make long hours without proper ventilation or air conditioning and are paid too little to properly feed themselves. Also workers are subjected to verbal and psychological harassment and violence, especially the majority of women in the industry, who additionally potentially face gender based violence and sexual harassment.

- Workers sandblasting jeans with no safety equipment.

- Ali Enterprises worker's protest, Pakistan - 2012

- Tazreen Factory Fire, Bangladesh 2012.

What we do

Immediately after the Rana Plaza collapse of 2013, in which 1,134 workers were killed, we were involved in the establishment of the legally binding Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh. This programme has been so successful in making factories safer that brands and unions decided to continue the work after its first five year mandate ran out. As witness signatories to the Accord we critically follow brands’ interaction with the Accord (see for example this report), campaign for brands to join the programme and campaign for its work to continue. Because of the Accord’s clear successes in making factories safer, unions and labour groups in other countries such as Pakistan are now looking into how the example can be adapted to national circumstances in other countries.

Our goal is to make sure that mass disasters like Rana Plaza will never happen again. But workplace injuries and deaths can never be entirely prevented. Therefore we want to make sure that workers receive full and fair compensation for their medical costs, loss of income, and pain and suffering if they do get injured on the job. Governments, brands, retailers and employers must all take their responsibility. In the cases of the mass disasters at Ali Enterprises, Tazreen and Rana Plaza we have fought long struggles to make sure that brands pay into funds to provide compensation to affected families. This is particularly important in absence of national social security systems that live up to international standards. In Bangladesh, we are therefore advocating for the establishment of a national employment injury insurance scheme.

Many dangerous practices in garment factories are hidden deep in supply chains. Brands should be aware about these potential violations, actively address them and allow workers and activists to help in this process by making their supply chains more transparent. The solution starts with awareness and the willingness to address problems. An example is our campaign again sandblasting, which led to over forty brands pledging to eliminate sandblasting from their supply chains. Eventually promises however are not enough; the most pressing problems in global supply chains should be addressed through enforceable agreements through which brands make themselves legally accountable to improve safety in their supply chain.

Background

The Rana Plaza collapse of 2013 functioned as an eye opener for the garment industry and accelerated processes that had started years before to address the problem of dangerous workplaces in Bangladesh. The establishment of the Accord, only weeks after the collapse, was a departure from the corporate-led voluntary, commercial system of auditing that had failed to prevent the mass disasters of the months, years and decades before. Truly sustainable safety in the workplace can only be reached if workers can address their own safety freely and refuse unsafe work, without fear of dismissal (see the report Our voices, our safety). Ultimately, full freedom of association is the only safeguard to that, but the Accord has been also been instrumental in empowering workers through their training programme and complaint mechanism. The successes of the Accord in reaching a transparent and enforceable programme to address factory safety confirmed our belief that that better regulation, inspection and enforceable brand agreements are the way forward for the industry. Over the years the Rana Plaza anniversary has become a moment of reflection to sum up the situation in the garment industry, especially in Bangladesh.

Sandblasting, a method to make jeans look old or pre-worn using pressurised air and sand, is extremely dangerous for workers as it causes fatal silicosis and other respiratory diseases. As a network we have exposed the use of these methods in supply chains in a range of reports in 2010, 2012 and 2013. Our Killer Jeans campaign convinced over forty brands to ban sandblasting from their supply chains. Nevertheless up until today deeply hidden in supply chains sandblasting continues to occur, as well as alternatives with their own hazards, such as the use of chemicals for the same worn look. Research, media attention and training therefore continue to be needed and our network will continue to raise these issues.