COVID-19 continues to ravage the health and livelihoods of garment workers

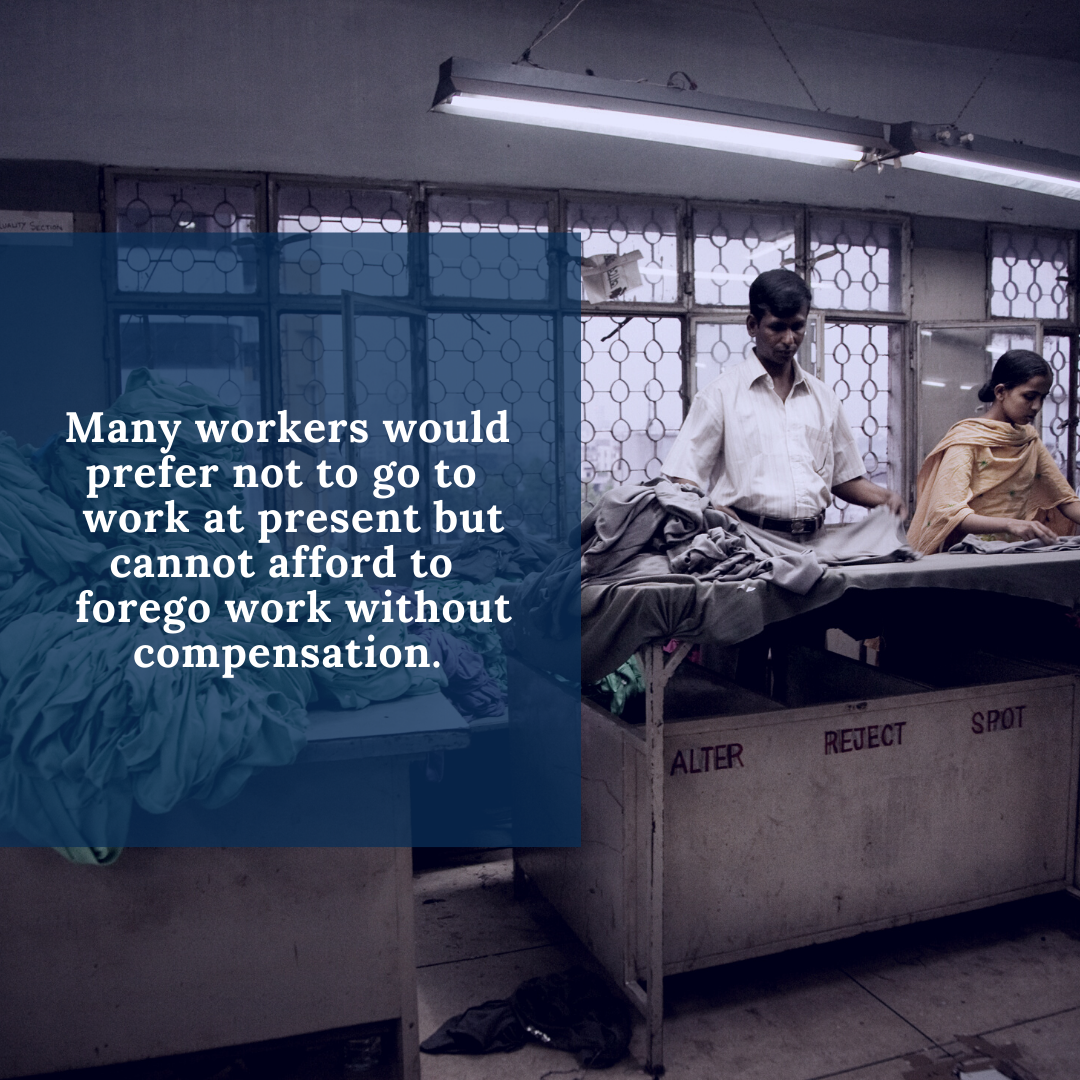

The global COVID-19 pandemic continues to grow and spread. Half of the world’s population is under some form of lock-down or movement restriction in order to control the spread of the novel coronavirus. Garment workers in global supply chains, who already grapple with poverty wages and precarious living situations, face increasing insecurity as factories close in response to steep drops in orders and as governments shut down manufacturing to protect public health.

Garment workers have been hit by each of the three waves of this pandemic. First, when China identified COVID-19 in its population, the country largely stopped exporting raw materials needed for garment production. As a result, many factories in South and Southeast Asia closed temporarily and sent workers home, often without notice or wages. The next wave hit as the virus arrived in Europe and the United States. Apparel companies cancelled in-progress orders without payment, and many stopped placing future orders. Supplier factories, which operate on thin margins due to the low prices paid by apparel brands, were forced once again to close and send workers home without pay. The latest wave is still crashing, as the novel coronavirus spreads in these countries. Some countries have closed garment production facilities as a precautionary measure – once again sending workers home without pay. Others have remained open, despite the significant health risk to workers in densely-packed factories.

Anton Marcus, Joint Secretary of the Free Trade Zones & General Services Employees Union, said: “The impact of COVID-19 on garment workers in Sri Lanka has been immense. Workers had to return to their villages without their March wages and are therefore having very a difficult time. They are breadwinners, but cannot support their families. Employers are making use of this situation to lay-off workers and curtail employees’ benefits and income by stating that their customers have withdrawn or reduced their orders. In this situation contract workers will be hit the hardest.”

In some cases, these effects have been exacerbated by national governments’ poor crisis management. India announced a national lock-down suddenly, leaving domestic migrant workers without livelihood or access to transport to return home when many lost employer-provided housing. Some migrant workers were forced to walk hundreds of kilometres to their home towns and villages. In other countries, such as Cambodia and the Philippines, measures to fight the virus further limit civic space, including workers’ freedom to organize. In Myanmar, factory owners have used the pandemic as a pretext for union-busting, making sure that union members were the first to be dismissed by factories in financial trouble.

Two recent papers by Worker Rights Consortium, the Penn State Center for Global Workers’ Rights and Clean Clothes Campaign, “Who will bail out the workers that make our clothes?” and “Abandoned? The Impact of Covid-19 on Workers and Businesses at the Bottom of Global Supply Chains”, highlighted the root causes behind the catastrophic effects of COVID-19 on supply chains. The extreme interconnection and unequal balance of power in supply chains caused brands and retailers to offload the consequences of declining demand for fashion on their suppliers. Apparel companies only pay upon delivery – with factories fronting costs for factories and labour – and have the power in the supply chain to enforce a decision not to pay if it means de facto breach of contract. This means factory owners around the world are left strapped for money to pay their workers’ wages, even for March and even less so for months to come in which no orders might come in at all. In the vast majority of garment producing countries, social protection mechanisms such as health insurance, unemployment insurance or guarantee funds in case of insolvency are absent or insufficient, partly due to decades of downward pressure on the prices paid for garments. Years of failure to take meaningful action on wages have left workers with no savings.

Since the publication of these two papers, a small number of brands have agreed to fulfil their contractual obligations and pay for the orders that factories are already in the process of producing. H&M, PVH Corp., which owns Tommy Hilfiger and Calvin Klein, Zara-owner Inditex, and Target have all agreed to pay for finished or in-production orders.

Ineke Zeldenrust, Clean Clothes Campaign, says: “We call upon other brands to also confirm publicly they will pay for orders that they placed themselves, which are often already produced. Urgent action is needed to ensure that all workers continue to receive their legally mandated wages and benefits, and have sufficient income so they and their families can survive this crisis. Brands and retailers have built their profits on the underpaid labour of workers, knowingly sourcing from countries with insufficient social protection floors. Any action taken now must lay the foundation for the structural changes required in supply chain regulation and legislation both globally and nationally. “

International financial institutions are already pledging to mobilize billions of dollars to support the economies of producing countries. It is critical that such support comes with commitments to put the needs of working people first and mechanisms that ensure this support reaches them. The Global Unions have issued recommendations for how these institutions can ensure an urgent and equitable response to the crisis. It is of utmost importance that workers, both in the factories and those working in retail or distribution, are at the centre of economic solutions in this crisis, to ensure that measures to safeguard people’s health are not leading to their destitution instead.